This article will focus on the three known die varieties for the 2 centavos issue.

| Variety 1: | large cap and large rays; legend letters and digits with a block style in shape with reasonably consistent position and spacing. Rays around the cap are bold and have consistent spacing. They are also symmetrical in appearance around the cap. |

| Variety 2: | medium cap and short rays; similar legend letter and digit styles as Variety 1 except some have rounded features with fairly consistent position and spacing. Rays at the base of the cap are sparsely spaced and have inconsistent length compared to Variety 1. |

| Variety 3: | small cap and short rays; legend has inconsistent and rounded letter and numeral sizes (tall and short), spacing (wide and narrow) and position (angled or straight up and down). Rays at the bottom of the cap are very short and almost non-existent. |

Variety 1 is catalogued in Mexican Revolutionary Coinage 1913-1917 by Hugh S. Guthrie and Merrill Bothamley{footnote}Guthrie, Hugh S., and Merrill Bothamley. Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, 1913-1917; based on the Bothamley Collection. Beverly Hills, CA: Superior Stamp & Coin Co., 1976.{/footnote} as GB-240 and was struck in copper with a plain edge. In the more recent publication, Compendio De La Moneda De La Revolución Mexicana by Carlos Abel Amaya Guerra{footnote}Amaya G., Carlos Abel. Compendio De La Moneda De la Revolución Mexicana. Monterrey, NL México, 2010.{/footnote} this coin was catalogued as A-JL 5 (thin planchet) and A-JL 6 (thick planchet). Variety 2 in copper with a plain edge was unknown and not catalogued by Guthrie and Bothamley; however catalogued by Amaya as A-JL 8. Variety 3 in copper with a plain edge was also unknown to Guthrie and Bothamley, but catalogued by Amaya as A-JL 9.

Variety 1 Large Cap & Long Rays Variety GB-240, A-JL 5 (thin planchet) or A-JL 6 (thick planchet)

Variety 2 Medium Cap & Short Rays Variety GB-UNL, A-JL 8*

Variety 3 Small Cap and Short Rays GB-UNL, A-JL 9

All three varieties were struck in copper with a plain edge. There is no evidence that there were any struck in brass or with a reeded edge. All 2 centavos are basically the same approximate size in diameter (20mm), but weight varies from 3.00 grams to 5.50 grams due to the crude minting practices at the time which produced inconsistent size planchets. These are often times referred to as thin planchets or thick planchets depending on the weight.

The mintage for each variety is unknown as with most coins from the revolution. It is also not known which of the varieties was minted first. It seems most likely that Variety 3 came first since it is the crudest in quality and design of the three varieties. Variety 2 was probably minted about the same time; however, it has a much improved, more refined design than Variety 3. It is possible that Variety 2 and Variety 3 were early trial strikes or possibly crude, quickly designed early issues. Variety 1, more than likely, was the last to be produced since it shows the best quality and most refined design. It is also the most common in quantity of the three known varieties. I speculate that once the Guadalajara mint became fully functional, the die for Variety 1 was produced with more care and attention to the die details compared to what was seen in the other two varieties and became the primary die used for the 2 centavos issue. This die design is also more consistent in style and design with that used for the 1 centavo and 5 centavos Jalisco coins issued around the same time.

Although there are numerous differences in the obverse dies of the three known varieties, it is the difference in the LIBERTAD lettering across the base of the cap which is the most easily recognizable while the rays at the base are the next noticeable.

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

As mentioned previously, the legend letters and numerals in the date are different and can help highlight some of the variety differences. Legend letter and numeral sizes, spacing and position are inconsistent and rounded in shape on Variety 3, while the letters and numerals are more uniform in size, block style in shape with relatively consistent position and spacing on Varieties 1 and 2. These differences are easily seen on closer examination of the letters “B”, “C”, “M”, “P” and “R” while the differences in the date (1915) is most easily seen in the digits “9” and “5”.

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

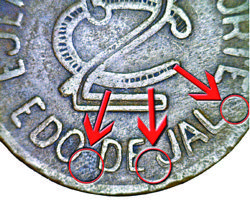

Like the obverse, the reverse legend lettering is quite different between the three varieties. The reverse legend also has another feature to help distinguish the varieties. Variety 1 has a period after EDO and JAL, but missing after DE, thus shows as “EDO.DE JAL.”. Variety 2 is missing a period after EDO, but has one after DE and JAL, thus shows as “EDO DE.JAL.”. While Variety 3 has no periods after EDO, DE or JAL, thus shows as “EDO DE JAL ”.

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

The letter “L” on Variety 1 reverse is different than Varieties 2 and 3. The “L” on Variety 1 has a small vertical notch at the back portion of the letter that is about half the length of the letter. This feature is missing on Varieties 2 and 3 where the letter looks like a normal capital “L”.

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

Like the letter “L”, the reverse Variety 1 has a similar feature on the denomination digit “2” which can be seen as a small vertical notch at the back portion of the digit. Varieties 2 and 3 do not have this feature.

Variety 1 Variety 2* Variety 3

Variety 1 (GB-240, A-JL 5 & A-JL 6) is a relatively common coin from the Mexican Revolution and can be easily found in online coin auctions and at dealers’ tables at coin shows for reasonable prices. These coins are usually seen in circulated condition; therefore expect to pay a premium for high grade and uncirculated specimens. On the other hand, Variety 2 (GB-UNL, A-JL 8) and Variety 3 (GB-UNL, A-JL 9) are rare coins and very seldom seen offered for sale in any condition.

At the height of the Mexican Revolution in 1914, Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco, was held by the Federal Army under the command of President and dictator Victoriano Huerta. The revolutionaries shared a common objective: to overthrow Huerta by reclaiming territories under his control.

A year earlier, Venustiano Carranza had declared himself “First Chief of the Constitutionalist Army” and organized seven military corps, appointing General Álvaro Obregón to command the Northwestern Army.

In June 1914, Obregón and his troops advanced toward Jalisco to capture the capital. The battle began on the morning of 6 July at Hacienda Orendain. Despite being outgunned, Obregón’s men steadily overpowered Federal troops under General Miguel Bernard, forcing a retreat. In Guadalajara, Huertista governor José María Mier, upon learning of the defeat, ordered an evacuation. On 8 July, Obregón’s army entered the city unopposed, and General Manuel M. Diéguez was named interim governor.

Crushing defeats — including the fall of Zacatecas to Pancho Villa — soon compelled Huerta to resign. However, this opened the door to a bitter rivalry between Villa and Carranza, plunging the Revolution into one of its bloodiest phases.

Pancho Villa was a charismatic leader who attracted followers from all walks of life. By mid-1914, his División del Norte (Army of the North) had grown to nearly 23,000 men, including peasants, regional caudillos, and even former Federal soldiers. From late 1914 to early 1915, Guadalajara was fiercely contested:

17 December 1914: Villa’s forces retook the city, expelling Carrancista General Diéguez and appointing Julián C. Medina as interim governor.

18 January 1915: Reinforced Carrancista troops under Diéguez recaptured the capital.

12 February 1915: Villa returned with his famed Dorados, defeated the Carrancistas, and reinstated Medina. Believing the region secure, Villa departed north to support Felipe Angeles, leaving the campaign in the hands of Medina and Rodolfo Fierro. But by 18 April, Carranza’s forces had permanently retaken Guadalajara.

According to Alejandro Cortina, in Boletín #167 (April to June 1995) of the Sociedad Numismática de México, 1, 2, and 5 centavo coins bearing the legend “EJÉRCITO DEL NORTE” were struck to pay Villa’s troops — possibly using a railroad car as a mobile mint.

In his 1928 work The Mexican Revolutionary Coinage, Howland Wood described and illustrated these Jalisco issues. He also documented a unique One Peso copper trial strike (Plate V, No. 56), similar to the 1915 Chihuahua pesos but with extremely faint peripheral legends — likely the result of an early die test.

Later, in 1933, J. Sánchez Garza, in his 1933 work Notas Históricas sobre las Monedas de la Revolución Mexicana, confirmed the existence of a second specimen, noting that General José Delgado had ordered the minting of 10 centavos coins at a provisional mint located in Guadalajara’s Archbishop’s Palace. The mint was overseen by Colonel Gilberto García, engraver Ramón Aguayo, and workshop chief Vicente Madrigal.

This 1915 peso from Guadalajara is a masterpiece of revolutionary coinage, based on the design of silver pesos minted from 1898 to 1909 (KM# 402), but with key distinctions:

Legend: EJÉRCITO DEL NORTE on the obverse and REPUBLICA MEXICANA on the reverse.

Value: UN PESO

Mintmark: Ga (Guadalajara)

Assayer’s mark: J.D. — likely referring to General José Delgado, who ordered the minting according to Sánchez Garza

This denomination was never officially released, likely due to the definitive loss of Guadalajara to Carranza’s forces in April 1915. No silver specimens are known — only a handful of copper trial strikes survive, showing the progression of die preparation.

It is also worth noting that the revolutionary pesos struck later that year in Chihuahua, by engravers Sevilla and Salazar, were clearly influenced by this design. From October to December 1915, Villa’s government minted silver pesos using bullion seized from the American Smelting and Refining Company’s plant in Chihuahua.

Since the first recorded appearance of a specimen in 1928, only two examples have surfaced at public auction and three more through private sales. Absent from key references such as Utberg’s The Mexican Revolution and its Coins (1965) and Gaytán’s La Revolución Mexicana y sus Monedas (1969) — and even missing from the Banco de México’s collection — this coin is regarded as one of the most elusive and coveted pieces of Mexican Revolutionary coinage. Even with optimistic estimates, fewer than ten specimens are believed to exist.